the legacy of peter anderson

By Joseph Press IV

In 1931, at the height of the Great Depression, American author and historian James Truslow Adams published a book called The Epic of America.

It was an ambitious undertaking, as Adams set out to chronicle the

entire history of the United States in 433 meticulously researched

pages. Upon its release, the book was extremely well received — an

international bestseller that garnered global critical acclaim.

Fundamentally, the book can be broken down into three composite parts:

1) The ethos of America, 2) The history of America, and 3) The

contradictions of America. It proved to be a timely piece that pinned

the historic success of the country to the tenets set out by its

aspirational founders while also highlighting the shortcomings and

structural failings that ultimately drove the nation into the Great

Depression. But overall, the tenor of the book was hopeful — for if the

leaders of the country earnestly attempted to rekindle the founding

principles, Adams believed that prosperity was well within reach. Those

principles were encapsulated in a phrase Adams coined in The Epic of America that endures to this day: The American Dream.

“… that dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and

fuller for everyone, with opportunity for each according to ability or

achievement… It is not a dream of motor cars and high wages merely, but a

dream of social order in which each man and each woman shall be able to

attain to the fullest stature of which they are innately capable, and

be recognized by others for what they are, regardless of the fortuitous

circumstances of birth or position.”

That was James Truslow Adams’ American Dream. But it was not his alone,

for what Adams articulated in his defining book was the dream of

millions of Americans suffering during the Great Depression, as well as

millions of future Americans yet born. Indeed, one such individual whose

remarkable life was driven by the goals and aspirations that underpin

the American Dream was born 18 years after The Epic of America

was published. And like so many proud and patriotic Americans before

him, he was born well outside of America’s borders, thousands of miles

across the Atlantic in a land far away. That man was none other than

former professional footballer and Luton Town legend, Peter Anderson.

Peter

Thomas Anderson was born on May 31, 1949, in Hendon, a parish in the

county of Middlesex that is today part of Greater London. He and his two

siblings, Sheila and Derek, were raised by their parents — Harry, a

truck driver, and Matilda, a seamstress — on a council estate in North

London called Friern Barnet. While growing up in post-World War II

England was challenging for most families due to the economic hardship

of the time, Peter enjoyed a joyous and carefree childhood. In fact, he

didn’t even realize that he and his family were poor until he attended

Grammar School as a teenager. Sure, the realities of working-class

struggle were present, but they never quite registered — for his world

was shaped not by what his family lacked, but by the determination of a

father who refused to let circumstance dictate the future of his

children.

“My father was a very bright man, but he had to leave school to work full-time when he was 14,” said Peter. “Back in the day, everyone had to contribute to the family funds, so he had no avenue to get a higher education and reach his full potential. In those days, only 1% of the population went to university. But the most important thing to my dad was to make sure that I did not have to be a truck driver like him. He had a hard life. And he made sure that I would be well educated and gainfully employed.”

Below: Friern Barnet in the 1950s

Most

English children in the 1950s and 60s attended primary school until the

age of 11, at which point they took a standardized test called the

11-plus exam to determine their next step in life — Secondary Modern

School to learn a vocation or Grammar School to further their academics.

Most children were streamed to Secondary Modern School, but Peter was

one of the exceptions and, to his parents’ delight, was admitted to

Grammar School. While his father did not have a specific job in mind

that he wanted Peter to pursue after Grammar School, he made it very

clear that it would be a profession of prestige.

“My

dad told me that I was going to get a job with letters behind my name.

It was the biggest thing to him — he thought if I had letters behind my

name, then I wouldn’t have to be a truck driver. So, at 16, I signed

articles of association with a firm of chartered accountants.”

While

accounting did not particularly excite Peter — for in his own blunt and

unvarnished words, he “just wanted to play football” — the lessons his

father taught him through the way he lived his life and the aspirations

he had for his family stick with Peter to this day. If you work hard,

play by the rules, commit to your craft, your community, and your

family, and above all, strive to be a good and honest person, you are

destined to live a successful and fulfilled life.

“I

always admired people who were loyal — to their team, to their work,

and to their country,” said Peter. “My motto, in football, business, and

life has always been ‘do the right thing.’”

That

unyielding sense of purpose drove Peter to success in the classroom, at

his apprenticeship, and eventually, as a professional footballer at the

highest level of the English game.

Like

most boys in 1950s England, Peter began playing football the moment he

learned to walk. To be fair, there wasn’t a great deal for young men to

do for recreation in those days — football in the fall and winter,

cricket in the spring and summer. But Peter’s affinity for the game

wasn’t borne of circumstance or boredom; his was genuine devotion, a

love both instinctive and unshakable. By the age of six, he knew he

wanted to play football professionally, and he dreamt of one day

following in the footsteps of legends like Jimmy Bloomfield, David Herd,

and — his favorite player — George Eastham.

“Football

was my whole life — it’s all I did. Go to school, come home, do my

homework, then go out on the street of the estate and play football with

the boys. And I was pretty good.”

As

it would turn out, Peter proved to be more than “pretty good.” He

excelled at every level of organized football: in primary school, at

youth clubs, and in professional development academies. Peter rose

through the ranks with a quiet inevitability, his talent unmistakable.

After transitioning from Grammar School to an accountancy apprenticeship

at 16, a Watford scout named Frank Grimes saw Peter playing for a local

team, visited the Anderson family home, and offered Peter the

opportunity to attend a tryout for the club. At the time, Watford was in

the third tier, but it was still a step up in competition for young

Peter. After playing for Watford for a year, Peter moved to Wealdstone

FC for a short period, then to his hometown club, Barnet, and finally to

Hendon.

Wealdstone,

Barnet, and Hendon were all amateur at the time, but the standard of

play was rigorous and the competition fierce. Semi-professional clubs in

those days often featured several former pros who still had pride in

their craft and enough left in the tank to make life difficult for the

younger generation. Nevertheless, Peter continued to impose himself on

the game and rise to the demands of tougher competition on the pitch.

His efforts did not go unnoticed, and one day, as if plucked from the

script of a fairy tale, Peter received a phone call from Harry Haslam,

then chief scout of Luton Town Football Club. At the time, Peter had no

way of knowing that his life would never be the same.

“It

was very quick, how I became a professional…” said Peter. “It started

with a phone call one Monday while I was at work — remember, I’m wearing

a pinstripe suit doing spreadsheets and budgets for corporations! So I

get the phone call, and my dad drives me in our little three-gear Ford

car about 40 miles up the motorway north of London to Luton. We get out

of the car at Kenilworth Road, and they were playing a Dutch team in a

friendly. There weren’t that many people there, only 8 or 9 thousand —

but it was a big deal for me at the time. So Alec Stock — an incredibly

well-dressed former war hero who was revered as a football coach — meets

us at the grounds and takes us to the locker room. After changing into

the Luton strip, he tells me to watch the game with him on the

sidelines. So I sit next to him on the bench and watch the game until

halftime, and we’re going into the break down 2–1. When we reach the

locker room, he turns to me and says, ‘In the second half, enjoy

yourself — go on and play.’”

And

with that, Peter Anderson, age 19, was set to make his debut for Luton

Town on a minute’s notice. “When I went out for the second half, the

first 15 minutes were a blur; the game was played at lightning speed. I

was in at right wing, and all I was doing was watching the ball whir

past my head from one end of the pitch to the other. It was all so

quick. I thought, ‘I’m never going to touch the ball!’” But then,

seemingly out of nowhere, the game slowed, the moment clarified, and

everything changed.

“After about 15 minutes, the left winger had the ball, crossed it, everybody missed it, I ran onto it and thought, ‘I’ll shoot.’ And it flew into the top corner of the net!” Peter had scored his first goal for Luton Town 15 minutes into his trial and debut with the club. Now everyone’s eyes were on him. He handled the additional attention and pressure with poise and aplomb — exactly the opposite of what one would expect from a 19-year-old amateur. He had unofficially announced his arrival at Luton Town in the most emphatic way possible — but what would he do for an encore? The 8,500 strong at Kenilworth Road did not have to wait long to find out.

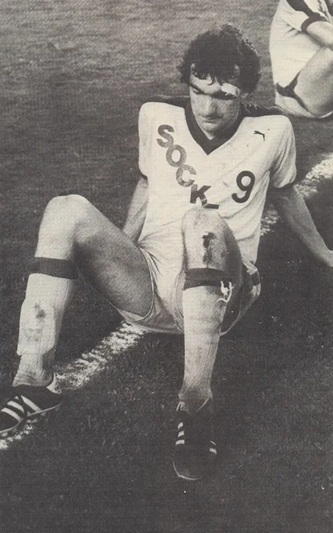

Below: Peter Anderson about to shoot

“Ten minutes before the end of the game, with the score tied at 2–2, I

get the ball feeling a bit comfortable and confident,” said Peter. “I go

at the fullback, who dives into a tackle and misses, then I go at the

center-half, who also dives into a tackle and misses. And then the

keeper comes out and dives five minutes before he’s anywhere near me —

now he’s on the ground too. So I just dribble around him and walk the

ball into the net, and we win 3–2.” Returning to the locker room after

what was probably the greatest trial in the history of Luton Town

Football Club, Peter was immediately confronted by the manager.

“Alec

Stock comes in and he goes, ‘Peter…’ — in his very upper-class voice —

he says, ‘Peter, your father is in the director’s room, and they want

you to go up and join your father.’ Now, my father was a truck driver.

He’s never made more than 20 pounds a week in his life — 1,000 pounds a

year. And when I got to the room, they had given him a whiskey and a

cigar; and they had cornered him. And they had a brown paper bag full of

money for me to sign for Luton Town right there.”

This

was the moment Peter had dreamt of — the moment he had worked towards

his entire life. After years of plying his trade and honing his craft as

a toddler on the estate, as an adolescent in Grammar School, and as a

teenager in the amateur leagues, the chance of a lifetime was staring

Peter right in the face. The lessons his father had taught him about

hard work, dedication, commitment, and self-discipline had been applied

consistently, without fail, day in and day out, for 13 years, and it had

all finally paid off. But then, in a moment that would shape his life

in ways he could not yet understand, it was snatched away from him. “My

father said no. Because I was under 21, I had to get his permission to

sign. The contract was 60 pounds a week, plus bonuses — he had only ever

earned 20 in his life — and there were 4 or 5 thousand English in that

bag. He said, ‘My son will shake hands with you on the deal, but he’s

going to get letters behind his name before he signs it.’”

And

so, with the firm and unshakable will of a working-class man who had

seen too many dreams vanish in the face of economic hardship, Peter’s

dream of professional football had been deferred. Peter, for his part,

was devastated. “On the way home, I never talked to him. I was so mad — I

wanted to be a professional footballer. But my father made it clear,

‘You’re not going to do it.’ And that’s what my dad did for me.”

Although

Peter had to wait two additional years to become a full-fledged

professional footballer, he began training and playing for Luton in

1969, shortly after his fateful trial. During that period, he also

continued playing for Hendon in the amateur leagues and worked towards

his accounting charter as an apprentice at a local firm. While Peter was

determined to fulfill his childhood dream of playing pro football, he

never held any animosity or resentment towards his father for

intervening at that crucial moment. On the contrary, he would come to

see it as one of the most important decisions of his life.

“It’s

very interesting how times have changed. After the initial shock, I

never gave it much thought. I knew he did it because he loved me. With

the accounting charter, I had a backup plan if football didn’t work out —

an insurance policy. More importantly though, after I retired from

football, my training and skills as an accountant gave me the tools to

start and run businesses. The wealth my family has today did not come

from football, but from the businesses we have been involved in. So, in

the end, it was the right call.”

Clearly,

the hard skills Peter learned through his accounting apprenticeship

served him well long after his footballing career ended. But, perhaps

more valuable than his mastery of bookkeeping and practical financial

management was the reinforcement of the core values first taught to him

by his father — honesty, discipline, and integrity. “It sounds silly

now, but back in the day, the people who ran accountancy practices

believed that your handshake was your bond. I remember when the guy I

signed my articles to shook my hand and said, ‘Anderson, this is the

most important thing — your handshake.’ This is what matters — you do

what’s right.”

After finishing his accounting apprenticeship in 1970, Peter was ready

to fully commit himself to his first and only true love at the time —

football. So, when the time came to make his pro debut against Watford

in February of 1971, Peter was ready to meet the moment. And how could

he not be? After all, his game had been sharpened for years on the

practice pitch, working with coaches and mentors, preparing for that

inevitable breakthrough. “When I first joined Luton, over a year before

making my professional debut, I spent hours and hours training with

assistant manager Jimmy Andrews. He was truly phenomenal. He’d take us

into a little gym and just practice headers over and over again. And

even before Luton, when I played at Barnet in the amateurs, it was the

senior players who took me under their wing. Gerry Ward, a former pro

who played for Arsenal in his prime, was hugely impactful. He used to

coach me through a game and help me with my decision-making on the

pitch.”

Peter, ever the sponge, soaked up all of the guidance and advice given

to him over the years to quickly develop into an invaluable part of

Luton’s midfield. He always had a talent for passing the ball and

finishing chances — for he was a winger when he played in the amateurs.

But after his body fully developed in adulthood, he used his newfound

physicality and ability to read the game to dictate the tempo in center

midfield, becoming the kind of player who could change the rhythm of a

match in an instant with a timely run into the opposition box and a

clinical finish when his team needed him most. For he was no longer reacting to the game — he was shaping it.

Below: Peter Anderson has the defender on toast.

Peter’s

first three years as a professional for Luton Town saw the club finish

solidly mid-table in the Second Division of English football at the end

of each season. They certainly weren’t a weak team, but they weren’t

particularly strong either. They were just… average. But everything

changed in 1973 when the club, seemingly overnight, transformed from a

side consigned to mid-table anonymity into one with genuine ambition.

After

a 12th place finish in the Second Division in 72/73, most pundits and

prognosticators predicted another mediocre season for Luton in 73/74 —

but the Hatters had other ideas. “Going into that season Luton were

probably 20-to-1 outsiders to get promoted. We were a blue-collar team,

and there were some very good teams in the league at the time. But we

felt early on that we had a pretty good shot at promotion,” said Peter.

Despite

Luton’s mid-table form of the previous two seasons, they were an

exceptionally talented side with a coach who had meticulously acquired

the right pieces at the right time. “After Alec Stock left, Harry Haslam

got the job in 1972. He was an avuncular guy, like everyone’s favorite

uncle. Unlike most English managers at the time, he wasn’t a ranter — he

never got too upset. And while he wasn’t a tactician, he was excellent

at transfers because he had previously been a head scout. He knew

everybody. So he brought in John Aston from Manchester United. Aston was

the man of the match in the European Cup final in ‘68! Then we got

Bobby Thomson, who was an English international. So, by 1973, all the

pieces of the puzzle had come together, and we had a pretty good team.”

After

a disappointing 4–0 loss to Nottingham Forest on August 25th to kick

off the season, one could be forgiven for thinking that the 1973 team

was no different from years past — that this was the same old Luton. But

when Luton returned to Kenilworth Road a week later to face Carlisle

United, they were prepared to put the entire league on notice: this was

not the same old Luton — this was a team with ambition, fire, and

something to prove. On September 1st, Luton beat Carlisle 6–1, scoring

each of their six goals before the halftime break. Peter, for his part,

scored his first goals of the season, contributing two clinical finishes

that left no doubt about his influence on the team. That performance

was the start of a 10-game unbeaten run; a run that put Luton solidly in

contention for promotion to the First Division by season’s end.

“As

the year went on, it became clearer and clearer that, unless we screwed

it up somehow, we had a good shot of promotion. So the games got bigger

and more important later in the season.” One such game took place

against Millwall on April 20th, 1974. At the time, Luton, Carlisle, and

Orient sat 2nd, 3rd, and 4th in the table respectively, with one point

separating each of them. Only two of the three would be promoted, as

Middlesbrough was comfortably ahead of the field at the top of the

league. Luton, coming off a loss to Oxford United three days earlier,

desperately needed the win. Fortunately for the 15,000 Hatters’

supporters at Kenilworth Road that spring afternoon, Luton saved one of

their best performances of the season for that decisive night when

everything was on the line. By day’s end, Luton had defeated Millwall

3–0, and the standout player was none other than Peter Anderson.

Luton’s

first goal of the game came from a Jim Ryan corner — a high, floated

inswinger with pinpoint accuracy thundered home by the head of John

Faulkner in the 8th minute. Then, just 10 minutes later, Peter received a

hopeful long ball delivered by John Aston and, with his first touch on

his weaker left foot, chipped the goalkeeper to make the score 2–0. It

is a goal he remembers fondly to this day: “I remember the goalkeeper — a

guy called King, good goalkeeper — came running out, and the ball just

sat up nice for me. Usually, I would try to dribble around him, but the

ball held up, so I just side-footed it over his head!"

For Peter, though, the joy he experienced from his own goal paled in comparison to the pure elation he felt when his close friend at the club, Gordon Hindson, capped off the day with the third and final goal of the game. “The best thing for me was seeing Gordon score. It was great! He took it from the halfway line, beat the offside trap, and took the chance really well. And I remember being so happy that I ran all the way from midfield just to hug him!”

The

unbridled joy Peter felt from witnessing Gordon put away the third

goal, and the warmth he exuded when recounting the story, are emblematic

of the selflessness and camaraderie with which Peter approached the

game. Individual accolades, like goals scored or assists tallied, were

certainly nice; but Peter always put the success of the team before

himself. “I always played for the badge first and foremost — that was

it.”

With the emphatic victory over Millwall, only one point was needed to secure promotion to Division One. That point was secured a week later on April 27th when Luton drew a stodgy affair against West Bromwich Albion at The Hawthorns. When the final second expired in extra time and the result was set in stone, the raucous celebrations began. Eric Morecambe, a comedian of national renown who also served on Luton’s board of directors, experienced the euphoria firsthand when he was thrown into the plunge bath by ecstatic players in the locker room post-game. Of course, that was only the beginning of the festivities, and what ensued from there became the stuff of club legend.

Below: Celebrating with Eric Morecambe

“We came back into town, went to various night spots, pubs, and bars, and had a good time. It was like floating on air for a few days. It was great. It was everything you wanted — a dream come true. It was fun, fun times.” But beyond the accomplishment of promotion to the highest level of the English game, what was especially meaningful for Peter was the bond he had with his teammates — a brotherhood forged in the heat of competition. “The camaraderie, above all else, was the best thing. You can never get that back. I always say to people, I’ve had successful businesses — we did well. But it was nothing like the locker room. It’s the one thing I truly miss about soccer. When I was done, I was done. I never looked back. But I never got the feeling of the locker room. The camaraderie you have with a bunch of guys that you spend a lot of time with, working together to achieve one thing, and then you actually achieve it — it’s a feeling that never leaves you.”

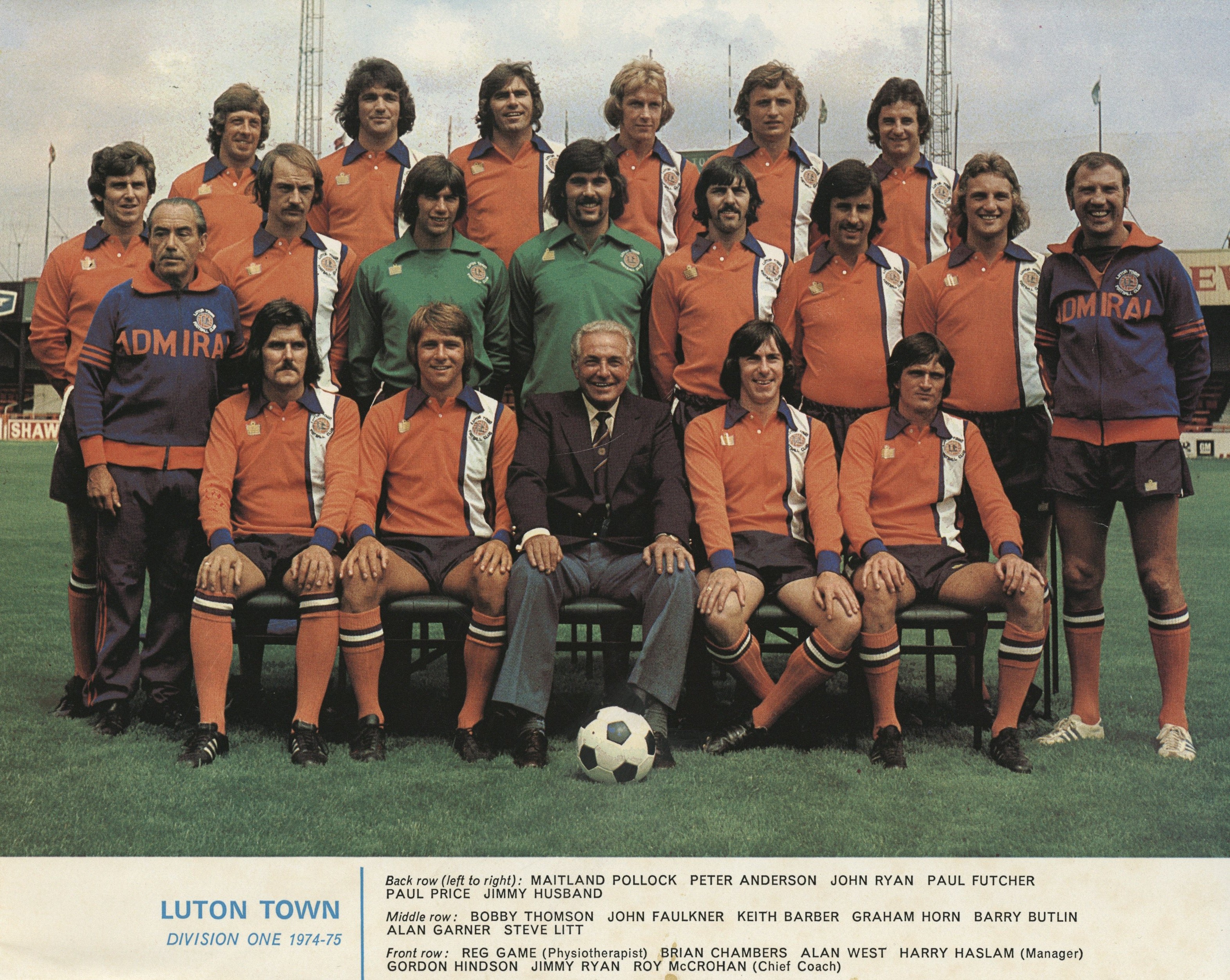

Below: 1974/1975 team photo

For a moment, it felt as if this dream would last forever. Unfortunately, the reality of the English First Division is not so sentimental. Instead, it is harsh, unforgiving, and merciless to those who cannot adapt quickly. Luton found this out firsthand upon their return to the top flight for the first time in over a decade. It wasn’t that they couldn’t hang with the top teams in the country, for they were almost always competitive when playing against the best sides in the league, but they too often fell short in the most crucial moments of games — moments that turn losses into draws, and draws into wins. Such was the case in their first game of the 74/75 season against perennial powerhouse Liverpool. “We played at home against Liverpool. We went a goal up. I had a chance from a corner, got up above everybody for a header, and thudded one against the post — two inches to the right and that’s a goal; we’d have been 2-nil up. They score two late goals — Tommy Smith scored from a free-kick that bobbled under the keeper, then Steve Highway scored. And that was the game.”

Below: Anderson heads wide against Liverpool

While

the first loss of the season was devastating for the team, pundits and

analysts sold it as a moral victory: “I remember everyone writing ‘it

was a valiant effort by Luton.’ Valiant. We all got ataboys and pats on

the back, but we lost the game.” As Peter and his teammates would soon

learn, “moral victories” are the currency of sides doomed for

relegation.

“Twenty

games into the season, we had nine points. We were so far bottom of the

league, yet we were losing 2–1 or 3–2. In the beginning, we felt like

we were the underdogs. ‘Little Luton.’ We thought that if we put up a

decent fight it was okay to lose. But it wasn’t okay to lose.”

Typically, in professional football, when a newly promoted team fighting

for their survival in a new league finds itself at the bottom of the

table halfway through the season, things get worse, not better. The

sporting director might fire the manager, money will be spent on loans

from abroad to strengthen the roster over the winter break, and despite

these efforts, the team actually sinks further into the pit of despair.

Luton, however, was not a “typical team” — they were a team built on

resilience, on the brash defiance of men who refused to accept their

fate. And so, they grit their collective teeth, strengthened their

resolve, and methodically went about the business of clawing their way

back up the table.

“It

took us until November to realize ‘we can play with these guys!’ After

Christmas, we actually won more games than we lost. We beat Arsenal. We

beat Leeds. We had a really good season.” Having relentlessly fought to

survive the murderer’s row that was First Division football and secure

their spot in the league for another season, everything hinged on the

final day.

“It

got down to the last game of the season — three went down, and we were

fourth from the bottom. Tottenham, who were one point behind us, played

Leeds at White Hart Lane. Leeds were top of the league, but were playing

in the cup final that following Saturday. So Leeds fielded their

reserve team, resting their starters for Saturday. Tottenham won the

game, and we went down.”

Unfortunately,

the end of Luton’s tenure in the First Division also effectively marked

the closing chapter of Peter’s time at the club.

“Sell the Accountant” was the title of a chapter in Alan Adair’s phenomenal book about his Luton Town fandom — Five Decades of Devotion to Luton Town F.C..

It is a reference to the sale of Peter Anderson to Royal Antwerp FC in

1975 — a cold but pragmatic financial decision worthy of its own chapter

because it saved the club from liquidation. The story of that fateful

transfer, from its bizarre genesis to its unexpected conclusion, is

truly one for the ages.

In the midst of the 75/76 season, Luton visited Charlton Athletic for a

midweek game at The Valley. Before the game, coach Harry Haslam told

Peter that he would not be starting in midfield — instead, he would

start at forward. While he thought the decision a strange one, ever the

consummate professional, he complied without question or dissent. The

move worked, as Peter scored a brace and played an instrumental role in

setting up the other three goals.

Below: Anderson rifles home in his final game.

It

was a phenomenal performance that showcased all of Peter’s strengths as

a footballer — his vision, his technical prowess, and his tactical

intelligence. Coach Haslam, apparently, thought so as well: “After the

game, I remember the boss being really happy. Then, there were the

directors — and they seemed really happy. Which is what I remember from

the whole situation.” As fate would have it, that was the last game

Peter ever played for Luton Town.

“The

next morning, I get a phone call from the boss, ‘Come into the office.’

When I arrive, he goes, ‘Peter, we’ve got a big bid for you from

Anderlecht.’ Now, Anderlecht were always in the Champions League, and

they were always champions of Belgium. So I thought, ‘Oh okay, that

sounds interesting.’ Then he tells me about a signing bonus. But I was

uncertain about the whole thing. So he says, ‘Let’s go on the plane and

at least talk to their people.’ Now, at this point, I don’t know that

Luton is bankrupt. So we get on the plane, just Harry and me, and we

arrive at Deurne airport… which is the airport for Antwerp. And there’s a

great big sign that says “Antwerp.” So I turn to the boss and say,

‘Boss, we’ve come to the wrong place.’ He goes, ‘What?’ I say, ‘This is

Antwerp. Anderlecht is in Brussels.’ He looks at me and goes,

‘Anderlecht… Antwerp… I knew it began with a fucking A!’ And that’s how I

got to Antwerp!”

By

fate or by farce, Peter was now in Belgium — and both Luton and Royal

Antwerp had every intention of keeping him there. “When we got to the

hotel, they wouldn’t let me leave until I signed the contract! It was

crazy. All their people were there, the manager was a guy called Guy

Thys — who was a fantastic person — and they were like, ‘Peter, we

really want you to come.’ So eventually, I signed. They just wore me

down. Then I was in Belgium — that was my next chapter.”

While

moving to Antwerp was not what he had envisioned, it ended up being a

great experience for Peter — he enjoyed the people and the city, and he

even learned to speak Flemish. Ultimately, though, his time in Belgium

was short-lived, and he moved to San Diego, California, to play in the

nascent North American Soccer League (NASL) after just two seasons at

Royal Antwerp. And for Peter Anderson in the late 1970s, moving to

America was a bold new adventure and the fulfillment of a long-held

dream.

Below: With the Sockers in 1978.

“I first came to the States when I was 21,” said Peter. “David Smalley, my best friend growing up, became a mathematics professor at Brunel University. One of his former students, a man named Chris Swain, got a job working at Heinz in Pittsburgh. I had just signed for Luton, and the offseason had just begun. So I visited Pittsburgh, and the three of us drove across America. I knew then that that’s the country I wanted to come to. America was blue and vibrant, and people were friendly. England, at the time, was the opposite — people were dour and grey, like the weather. And the country was losing itself in pity. But when I came to the States, everyone was working hard. They just wanted to get a better life.”

Peter’s affinity for the American people and the American way was inevitable, for the ethos of America reflected everything he stood for and believed in. When he arrived in San Diego in 1978, he wasn’t disappointed. “Playing in San Diego back in the 70s was fun. Bee Gees music was playing, everyone was happy, hanging out on the beach. I was able to meet a load of fantastic people. And I enjoyed my soccer as well.” Indeed, Peter scored a hat trick in his first game of the season for the Sockers. After one season in San Diego, he was sold to the Tampa Bay Rowdies — one of the top teams in the NASL. Peter’s three-year stint with the club included a single-season loan to Sheffield United — where he reunited with former Luton boss Harry Haslam — along with two soccer bowl finals in 1978 and 1979 and an NASL Indoor Championship in 1980.

Below: Anderson and Steve Wegerle at the Tampa Bay Rowdies

Peter

returned to England following the 1980 NASL season to serve as a

player-manager for Millwall. The team was, to his chagrin, in terrible

condition when he arrived. “Millwall were in an awful place

financially,” said Peter. “They had sold all of their decent players, so

they only had a bunch of kids. We were bottom of the Third Division. So

it was pretty dour.” Despite the bleak circumstances, Peter and his

staff helped save the side from relegation. After two more seasons in

the docklands, he left the club due to a contract dispute with

Millwall’s management that damaged trust between the two parties. “Once

the trust is gone, there’s nothing left,” said Peter.

After

leaving Millwall, Peter retired from professional football and took a

job at Nike to work on a team responsible for developing the company’s

first football shoe. “It was fantastic! I was mixing with many famous

athletes because they were in the advertisements!” Indeed, Peter’s time

at Nike saw him rub elbows with the likes of British world class

athletes like Steve Cram and Brendan Foster, sharing stories, laughs,

and good times.

Eventually,

Peter’s strong performance and growing influence led the company to

offer him a promotion that would have forced him to move to Northeast

England. With no connections in the region and no desire to uproot his

life, he turned down the offer and decided to return to Tampa for good.

Since

returning to Tampa, Peter has been involved in many successful business

ventures. Perhaps the most notable is Bayshore Technologies Inc. — a

company he co-founded in 1997 and helped build into a $40 million

information technology enterprise. And it was founded on the same values

instilled in Peter by his father all those years ago: honesty,

integrity, reliability, and hard work.

Today,

in retirement, Peter enjoys golfing with his friends, spending time

with his wife, Seretha, and visiting his two children, Allie and Jack —

who both live and work in Massachusetts. As he reflects on his

remarkable life, he is, above all else, grateful for the opportunities

he’s had, the experiences he’s cherished, and the wonderful people he’s

met along the way. And Luton Town FC, for its part, will always hold a

special place in his heart:

“I

was so blessed with my career, and I have nothing but good memories.

And I’ll always owe Luton a debt of gratitude because they’re the ones

that started it all.”

Below: Peter and family

Many thanks to Joe Press for allowing this article to be published on Hatters' Heritage. For more of Joe's brilliant articles, visit his Medium page.

Peter Anderson's profile page on Hatters' Heritage is here, and contains over 250 photos and articles.