john ryan - the most interesting man in the world

By Joseph Press IV

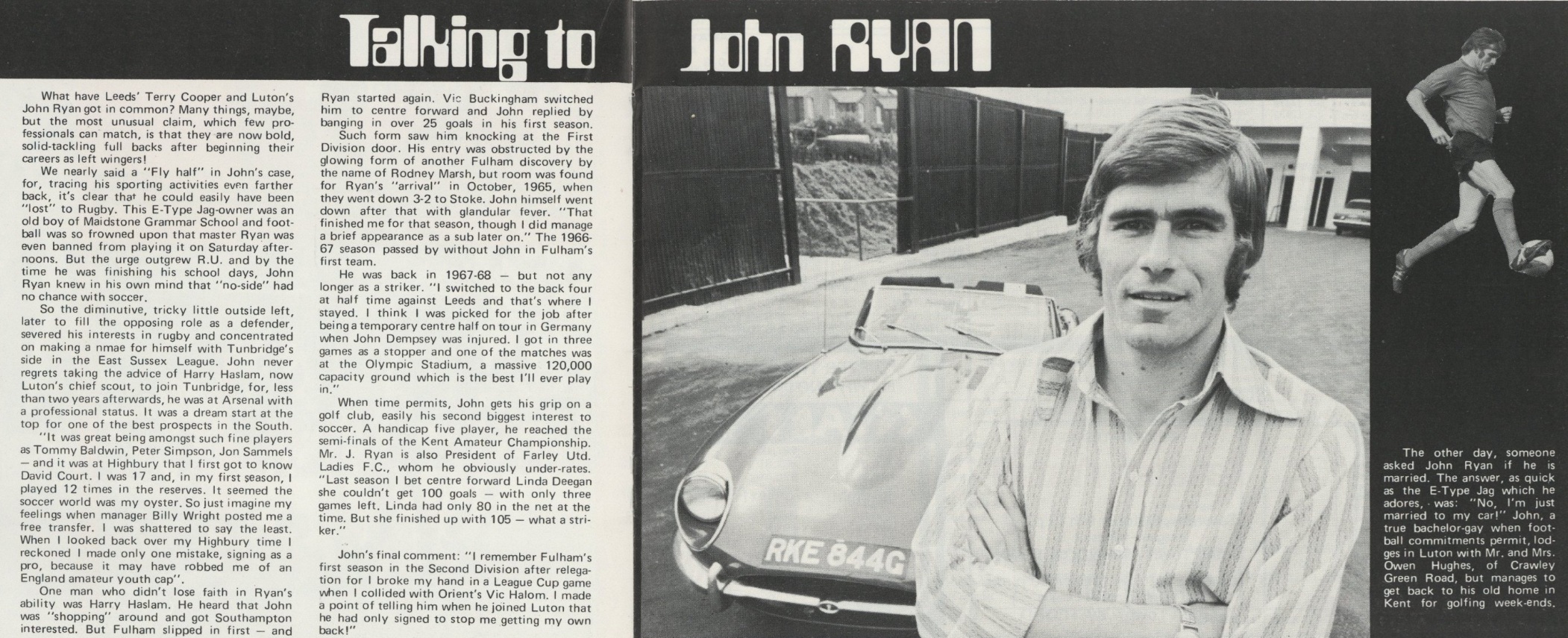

In 2006, Dos Equis, a Mexican beer brand under Heineken International, launched an advertising campaign called “The Most Interesting Man in the World.”

It featured actor Jonathan Goldsmith, who portrayed a charming, suave,

and adventurous older gentleman, and Will Lyman, who voiced the

narration in each of the commercials. Most of the ads began the same way

— with a video montage of Goldsmith’s character accomplishing a feat of

implausible élan, often with several onlookers agasp in stupefied

wonder — while Lyman narrated the scene with his distinctive, full-toned

voice:

“He’s been known to cure narcolepsy, just by walking into the room.”

“He once had an awkward moment, just to see how it feels.”

“His reputation is expanding faster than the universe.”

And then, after a perfectly timed pause, Lyman concluded his narration by matter-of-factly saying: “He is the most interesting man in the world.”

All

in all, the campaign was immensely successful, becoming one of the top

TV ads of its era. It reached the rarified air of unanimous acclaim and

recognition — parodied on mainstream programs like Saturday Night Live,

while also being imitated, referenced, and clipped by social media

influencers and content creators alike. Needless to say, it was a

brilliant alchemy of brand and myth — an advertising triumph disguised

as folklore. And what made it work, above all else, was Goldsmith’s

debonair gravitas — for through the absurd one-liners and winking

hyperbole, both he and Will Lyman gave their audience a taste of worldly

sophistication and humor. In truth, the latter was probably more

impactful than the former — as all viewers reflexively understood, upon

watching the commercials, that the “Most Interesting Man in the World”

was a carefully constructed fiction. He had to be — for there is no way

that such a person, equal parts Renaissance man and folk hero, could

possibly exist.

Yet,

the idea persists. For there are men who possess charisma, competence,

and courage, and who lead lives typically reserved for fairytales. Men

who not only accomplish the improbable, but do so with a style and

serenity that defy easy explanation. Men like Luton Town legend John

Ryan.

John Gilbert Ryan was born on July 20, 1947, to Sylvia Sayer and Joseph Slater — a fact he did not know until the age of 70, as he was adopted and raised by Elsie and Sydney Ryan at five weeks old. Elsie, John’s mother, was a woman of means who worked as a bus conductress. John’s father, Sydney, was the opposite — product of a very poor family of rascals, and a professional truck driver. But what Sydney lacked in formal education and social polish, he made up for with ambition, grit, and determination. “While he started out driving lorries and buses…” said John, “…my dad went on to be very successful. He wasn’t extremely rich; but he was wealthy.”

Below: Sylvia Sayer, John's Mother.

What started as a small-scale operation delivering furniture in and around Kent quickly evolved into a furniture delivery conglomerate. “At its height, my dad’s company was delivering furniture all over England, Scotland, and Wales. He ended up with 30 vehicles. They were big trucks — 36 foot long, 13 foot high — and he had 30 of them! So he did great.”

Below: Sydney Ryan, John's adoptive father.

Growing

up in Kent, young John was polite, charming, and affable — all prized

traits to his mother, Elsie, who always stressed the importance of

manners. As a boy, he had a natural aptitude for academics and

consistently earned good reports in the classroom. In fact, his

instinctive feel for language and arithmetic was so great that he was

among the few students in England to take the 11+ exams and do well

enough to matriculate into Grammar School. And once there, he had the

special distinction of being the only child in his class chauffeured to

school every morning.

“With

the haulage company, my dad had trucks, vans, and cars; and always

someone not doing anything to take me to school! So I used to say, ‘Park

‘round the corner.’ And I’d jump out around the corner and walk into

school,” said John. “The other kids soon found out. I was the posh kid

on the block.”

Despite

the ease with which learning came to him — and the first-class service

he enjoyed on the drive in each day — by the time John was accepted into

Grammar School, he had completely lost interest in formal education.

Instead, his focus was on his first and only love: football.

From a young age, and for as long as he could remember, John Ryan lived and breathed football. He was first introduced to the game by his father, who religiously took him to The Den to watch Millwall games. Sydney, for his part, had aspirations to be a professional footballer for Millwall in his youth — and he was quite good too, as he earned the opportunity to play a handful of games for the club. But a terrible knee injury prematurely brought an end to what might have been. So when John displayed both a passion and talent for football, his father was all in.

“Dad

wanted me to be a footballer. Then he started the youth program at

Maidstone United. So that’s where I began playing seriously.”

At

the time, Maidstone was an amateur side, and the most promising player

in their ranks was none other than John Ryan. “I was always better than

everyone else — at school level and at youth level… until I got to

Arsenal. Then I got a shock…” said John with a laugh, “…there were

people out there better than me!”

Johan

Cruyff once said, “Playing football is very simple, but playing simple

football is the hardest thing there is.” It was a tribute to the

footballer who masters the unseen rhythms — an homage to the disciplined

craftsmen. Indeed, it is not uncommon to find great footballers with

understated, subtle games who are often the most impactful players on

the pitch. Manchester City’s Rodri, for instance, did not win the Ballon

d’Or due to spectacular goals scored or assists piled onto stat sheets,

but for his preternatural ability to read the game like a coach on the

pitch, his flawless decision-making, and his surgical defensive work —

breaking up play with a timely interception or a deft touch, never

sliding into tackles or challenges.

John

Ryan was decidedly not one of these footballers. “I used to score

‘wonder goals’. So I would score regularly from 25 and 30 yards.”

John’s flair for the spectacular caught the eye of an Arsenal scout during the FA Youth Cup, when John was playing at Maidstone United. “I was playing for my dad’s youth team, and we were playing in the FA Youth Cup. When you start off, you play the local teams. So we played Dover, which was a Kent team, then we played Ashford; another Kent team. Against Dover I scored 4 goals and assisted 2. We beat them 6–1. The second game we beat Ashford 4 or 5. And I scored another 3 and assisted 2 more. So Arsenal had a scout there watching, and said straight away ‘you’d better come up,’ so I went up for a day’s training. And I played against a public school called Charterhouse. As you’d expect, we beat them 8 or 9 — and again, I scored a couple more goals, assisted a couple more. Then they said they wanted to sign me. At the time, I was too old to be an apprentice, so I signed full pro.”

Below: John Ryan (standing, 1st from left) with Arsenal's youth team in 1964.

For

most young men with aspirations of professional football, making the

cut at Arsenal Football Club would be a dream come true. While in the

early ’60s they weren’t the powerhouse they would eventually become in

the ’70s and ’80s, they were still a solidly mid-table side with a rich

history in the English game. And for a 17-year-old making the jump from

non-league football to the First Division on a day’s notice, playing at

the highest level was truly the opportunity of a lifetime… or so it

seemed. Unfortunately for John, timing was unkind — and the environment

colder still.

“Arsenal

had 44 professionals in the club when I signed. They ran 4 teams at the

professional level. I started in the third one. Before I left about a

year later, I played 18 games with the reserves — which was the second

team. It was full of international players, Irish, Welsh, and Scottish —

so I was doing alright!”

John’s

ascent to Arsenal’s reserves was swift and decisive, but the

opportunity to play first-team football never came. Instead, he had the

terrible misfortune of playing under a manager widely regarded as one of

the worst in Arsenal’s long, storied history. And to make matters

worse, that manager seemed hell-bent on freezing young John out of the

side and destroying his confidence.

“He

hated me!” said John. “He wanted his wingers — I was a left winger — to

hug the touchline and cross it with their left foot; which I could do.

But I found it just as easy to cut inside and shoot.”

John,

as fate would have it, was gifted with the rare ambidexterity of

two-footedness — he was equally comfortable with his left and right foot

— allowing him to break down defenders and score from virtually

anywhere on the pitch with his prodigious ball-striking ability. This

versatility did not particularly interest Billy Wright, Arsenal’s then

manager, who had a very doctrinaire way he wanted his wingers to play.

“We

went one day to play the Met Police — they played in some small London

league, nothing much. And Arsenal put one of their teams in it. And we

played, and these policemen were huge — so they were kicking lumps out

of us. I didn’t play well, and I wasn’t brave then.”

John,

just 17 at the time, was small and physically weak, having yet to reach

his athletic peak. “I was terrified! I had come from youth football,

and you didn’t kick anybody in youth football. And the first-team

manager happened to be there. We got beat 1-nil, which did not go down

well with him. And he got on the bus, looked and found me, and he

shouted to the rest of the team ‘Don’t talk to him on the way back. He’s

let you down today.’”

John’s

time at Arsenal mercifully ended shortly after that game in 1965. “Come

the end of the season, me and a couple of the other players were sat

one morning at breakfast and we each got an envelope. They got a great

big brown envelope. I got a little white one. They saw my envelope, got

up, and excused themselves. I opened my envelope and it was one telling

me I got sacked.”

While

John’s short tenure in North London was an education in the harsh

reality of professional football, it did little to grow his game — and

even less for his confidence.

“I

was still a kid…”, exclaimed John. “No one seemed to realize that I

didn’t know what I was doing! I did it because of a natural talent; but

that talent needed to be coached. The truth is I never got coached till I

arrived at Luton. I’d been a pro for 5 years then.”

Before

John could make his mark on the English game as a star for Luton Town,

his first stop post-Arsenal was in West London, at Fulham. And

fortunately for John, he didn’t have to wait long after his departure

from Highbury for the next opportunity to come along.

“Within about 4 days I signed for Fulham. The manager came down to my parents’ home in Maidstone, and said ‘I want to sign you.’ So I signed the contract.”

Below: John Ryan at Fulham.

The

timing couldn’t have been better — for if the call from Fulham had come

a few months later, the difficulties young John endured at Arsenal

might have taken a serious toll on his self-belief. Instead, buoyed by

the immediate faith of Fulham manager Vic Buckingham, and the confidence

and steady resolve instilled in him by his parents, John was ready to

kick on without hesitation.

At

Fulham, John experienced his first consistent spell of first-team

professional football — though how and where it came about was

unexpected, and less by design than he ever could have imagined.

Throughout

his youth career, John was primarily a goal-scoring left winger with a

quick first step and prodigious ball-striking ability. Upon his arrival

at Fulham, first-team coach Vic Buckingham sought to highlight that

clinical finishing by moving him to center forward. And in his first few

months at the club, it looked a masterstroke.

“Three

months after being moved to striker, I was scoring quite a few goals in

training,” said John. “And then, I remember it quite vividly, one day

on a Thursday morning in October we had a training match. And I had the

game of my life. First team played against the second team — I was in

the second team — and I played really well. Manager came over and says,

‘We’re taking you on Saturday to play in the first team.’ So within a

year of turning pro, I’m now playing in the First Division.”

It

was all coming together for John. After a brief setback under a poor

manager who didn’t believe in him, John Ryan was now set to play at the

highest level of English football. He was in great form, his confidence

at an all-time high, and he had a team and a coach who trusted his

instincts. This was the moment he’d been working all his life for — the

moment he’d dreamt of since childhood, when his father took him to see

legends like Charlie Hurley at The Den. But, as ever, fate had other

plans.

“I got glandular fever. I was in bed for 3 weeks, lost about 20 kilos. Didn’t play again that year in the first team.”

In professional football, the window of opportunity for a player to make his mark can close quickly. So a setback like the one John was dealt in October of ’65 would have been enough to fell many a promising athlete. But John was different. Resilient — almost as if channeling the unshakable work ethic he inherited from his father — he built his body stronger than before, continued to hone his game, and returned for the next season better than ever.

Now he just needed another opportunity to show what he could do.

“Come 1966 I was more reserve than first team pick,” said John.

Allan

Clarke was the starting center forward for Fulham at the time, and he

was on the cusp of a breakout season in which he would start every game

and score 24 goals. As such, for John, beating him out was unlikely.

Instead, his chance would probably have to come elsewhere on the pitch.

No matter — at this point in his young career, John was adept at playing

on either wing or through the middle. But, unbeknownst to him, his

position was negotiable.

“They

took me to Germany on a preseason tour. The center half was John

Dempsey and Allen was starting up front at center forward. We had a

little five-a-side match in the morning — I wasn’t going to play in the

evening game. I don’t know what happened between the two of them, but it

ended with Allen Clarke elbowing John Dempsey in the nose — breaking

his nose. So he couldn’t play. The club, looking around — this is so

Fulham — says ‘John, you’re the tallest player we’ve got left. You

better play centre half.’ I said, ‘I’m a center forward! I’m a winger!’ I

was still a kid, you see.”

Apparently, to Fulham’s management, age was but a number. And in professional football, when opportunity knocks for a young player trying to earn his spot in the pro game, he’d best be ready to answer the call. As the tens of thousands of fans in attendance at the Olympic Stadium would soon find out, John Ryan was more than ready.

“So

I’m playing in Germany against Hertha Berlin at center back. Every time

the ball comes to me I kick it in the crowd. And each time I booted it

out of play the manager and the bench cheered me on! If I miscontrolled

the ball or took a bad touch as a forward, I’d get a proper rollicking!

But now they’re cheering! Anyway, I did ok. I was quick and I could

tackle a bit. So I played the next 3 seasons at fullback.”

John Ryan the defender was born.

Between

1966 and 1968, John played in 47 games under managers Bobby Robson and

Johnny Haynes. He was a first-team regular, and had earned himself a

reputation as a utility man — capable of filling in at any position

across the backline at a moment’s notice. But when Haynes — who served

as caretaker manager following the sacking of Bobby Robson — was

replaced by Bill Dodgin, John’s playing time at the club quickly dried

up, as the new boss preferred a different profile of player at fullback.

No

matter — for as soon as John was released by Fulham, he was contacted

by Bobby Robson, who had just been hired by Ipswich Town to coach the

team. Robson and John had gotten along quite well from their days as

teammates, first, and then as mentor and protégé at Fulham.

“After

I got the sack at Fulham, Bobby rang me and said ‘John, come up and see

me — I want you to come to Ipswich.’ So I drove up to see him and I

asked for a signing-on fee.”

Because Ipswich sought to sign John on a free contract, he figured they’d have a bit of extra money to sweeten the deal.

“I only asked for 500 pounds…” said John, “…which in those days was nothing, really. Bobby said, ‘No, I can’t do that.’”

Before

he could dwell on the disappointment of a deal falling through with

Ipswich, another opportunity presented itself — at his favorite boyhood

club.

“After

that I went to Millwall, saw the manager there — someone had

recommended me to him. As I walked in, a player I knew from my days at

Arsenal saw me and said ‘Oh hey John! What are you doing here?’ I told

him I might sign. He said ‘Don’t sign here mate, it’s terrible!’

Now this was from one of their own players! In the end, it didn’t matter — they weren’t going to give me enough money.”

After

contract negotiations with Ipswich and Millwall fell through, John was

contacted by Harry Haslam — Luton Town’s head scout at the time.

“Happy

Harry had previously managed Tonbridge in Kent, so he’d seen me when I

was playing for Maidstone. And he told manager Alec Stock that I was

someone he should try and get.”

In

the late ’60s and early ’70s, an endorsement from Harry Haslam was

practically a guarantee you belonged in the Football League. As chief

scout at Luton, he was responsible for bringing in future stars like

Malcolm Macdonald, Peter Anderson, Jimmy Ryan, and Don Givens — each of

them crucial to the club’s rapid ascent up the English football pyramid.

To

that point in John’s young professional career, he had been little more

than a journeyman. His time at Arsenal was short and uneventful, and at

Fulham he was basically a rotational player. But at Luton Town — a

Third Division side with aspirations of something greater — John Ryan

finally found his footballing home. After arriving in Luton as a

22-year-old in 1969, John would go on to play seven years at the club,

make over 250 appearances — almost all of them as a starter — and play

an integral role in two different promotion-winning sides. In every way

that mattered, Luton Town and John Ryan were a match made in heaven.

From the moment John first arrived in Bedfordshire, he knew he’d found his place.

“I loved it! When I first went to Luton to play, I went into digs with a nice older couple — Mr. and Mrs. Hughes — who were lovely. And they were just short of the airport. I was a young man, just over 21 — earning good money — and Luton had an airport that imported 180 new air hostesses every February. It was a young man’s dream!”

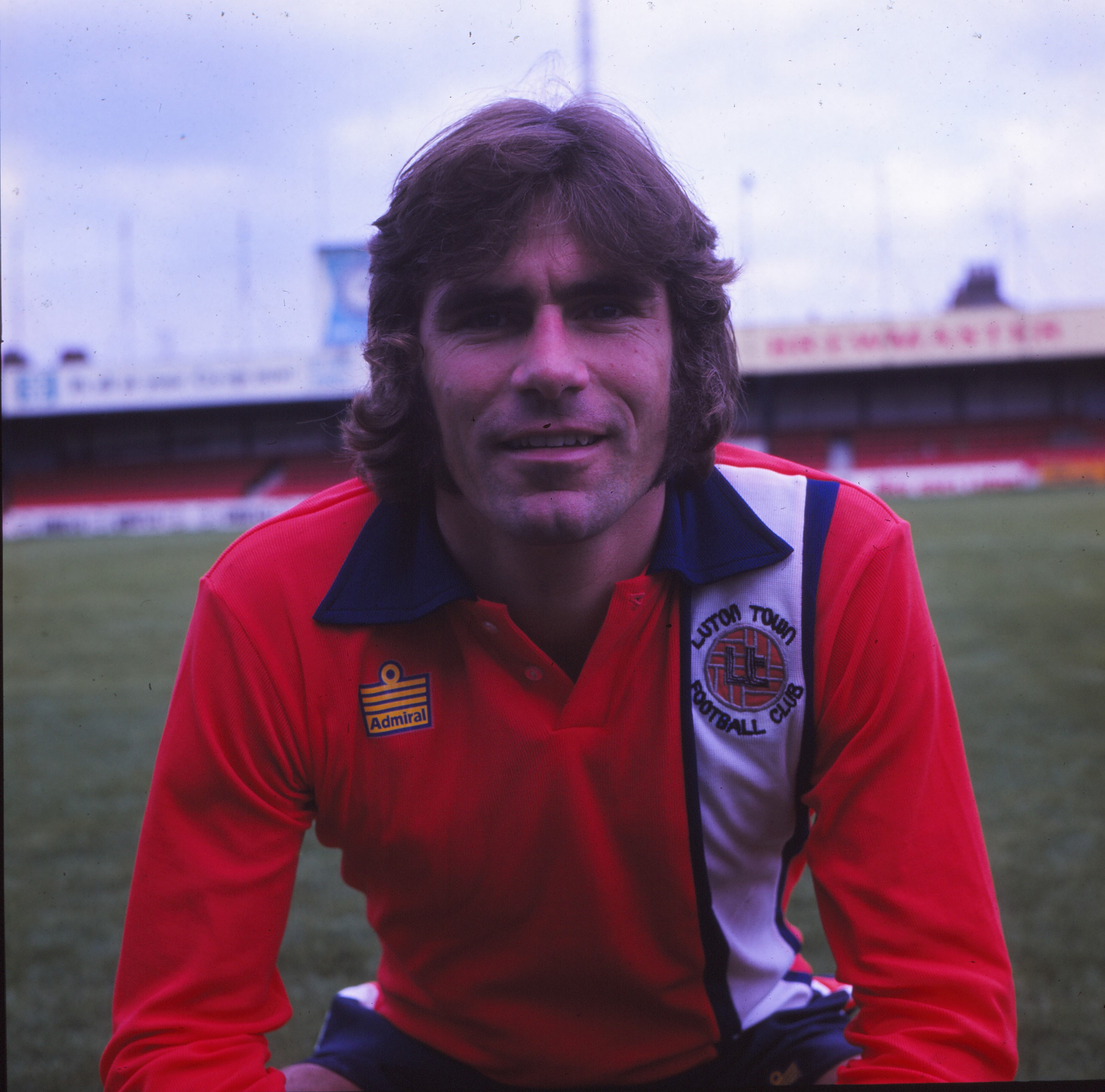

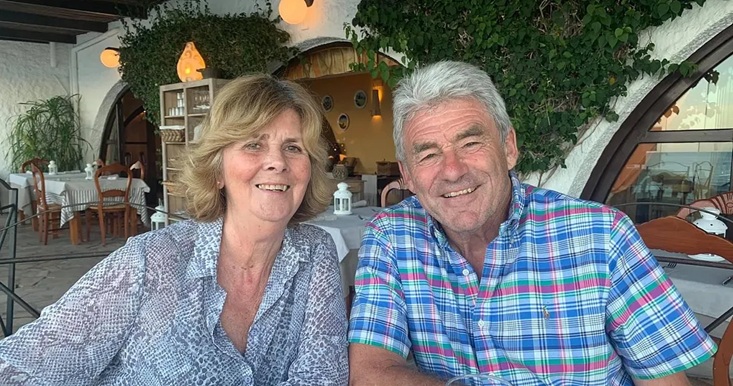

John was the very picture of the pro footballer as playboy — handsome, charming, quick-witted, and driving a fast cherry-red sports car; the Jaguar E-Type, to be specific. John’s wife of over 50 years, Kay — a former air hostess — can attest to just how notorious he really was.

Below: John and his Jaguar E-Type in 1971.

“Everybody

in Luton obviously knew about John — he was the playboy of town.

Everybody warned me against him. Because I was a stewardess I used to

drive to the airport and think, ‘Who on earth would park a red E-Type on

the side of the road like that!’ So my first impression of him was,

‘What an arrogant man!’ He was not my cup of tea at all.”

For Kay, the many stories she’d heard about John were confirmed when she first met him in person.

“I

lived in a house with several other stewardesses. And John phoned up

the house to see if one of the other girls would be willing to go

shopping with him in London to choose some clothes for his boutique.

Because he was going on tour the next day to Turkey. When he drove up to

my friend’s digs, he jumped over the windscreen and walked down the

bonnet. Now what would your impression be of somebody like that? It was a

joke! I’d heard all about him. Anyway, he asked my friend and I to go

to London with him to shop for clothes. We agreed. The next day he

started sending me one carnation every day through a florist.”

While Kay had many doubts about John’s fitness as a partner, John immediately knew that Kay was the woman he wanted to marry.

“I had been out with so many girls…” said John, “…and suddenly I had met a woman.”

John, ever the romantic opportunist, made his intentions clear after their first date.

“On

a Tuesday after coming home from a flight, I ran into him in the Flying

Club. He invited me to join him at a party that evening. I declined, as

I wasn’t dressed for the occasion. Then John said to me, ‘Can I take

you out to dinner?’ So we went to dinner that Saturday and he asked me

to marry him.”

Kay,

equal parts surprised and unimpressed by John’s confession of love,

resoundingly rejected him on the spot — “Absolutely not” — for she was

well aware of John’s romantic exploits both in Luton and Kent.

“He had a serious girlfriend in his hometown for four years when he first asked me to marry him. I didn’t want to be involved in anything like that. I also knew a lot of the stewardesses from the airport that had been out with him.”

John, completely unfazed and undeterred by this rejection, was determined to make it happen.

“I was in the hospital with what the doctors believed to be typhoid the very next day,” said Kay. “While I was in the hospital John had introduced himself to my parents, and, when I finally recovered, I woke up to a wedding ring by the hospital bed with a note that read ‘Please, will you marry me.’ The nurses said, ‘You’ve got to! He’s got so many parking tickets from that car of his.’ And a few months later we were married.”

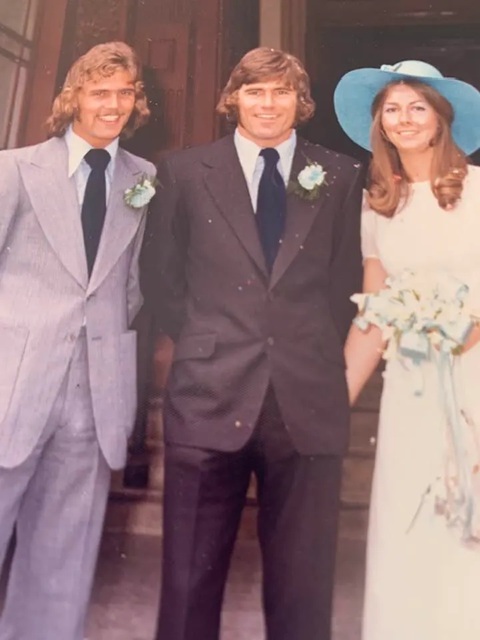

Below: From L to R Viv Busby, John Ryan and Kay Ryan at John and Kay's Wedding.

When

asked what the turning point was from “absolutely not” to “yes,” Kay

responded with one word: “persistence.” In the same way that persistence allowed John to overcome the disappointment at Arsenal and the instability at Fulham to find his Eden in Luton, persistence

helped him win the heart of the only woman who ever truly grounded him.

Fifty-three years, two children, and four grandchildren later, John and

Kay are still married to this day.

While

John’s social life in Luton was the stuff of local legend, the start of

his footballing career there was far more uncertain.

“The first 6 games I played were terrible. I got left out. Alec Stock — who was the manager at the time — said, ‘You’re not doing it.’ For the first time in my career, I thought ‘maybe I’m not cut out to be a professional footballer.’”

In

a moment where many athletes would collapse under their doubt and

self-pity, John harnessed it for motivation. He always had exceptional

ball-striking ability as a crosser and goal-scorer — now he would couple

that with a work rate the likes of which the Third Division had never

seen.

“I got myself some running spikes and went back every afternoon on my own and ran different distances — never more than 70 yards — but everything was flat-out. I built up my power and running speed and got back in.”

After

working his way back into the starting lineup, John received the one

thing that had eluded him for his entire career: coaching. And it

changed his career forever.

“Jimmy Andrews started to work with me. ‘When the ball is over there, you need to be here.’ That sort of thing.”

It

sounds simple, but oftentimes simple is best — especially for a player

who was receiving genuine tactical instruction for the first time in his

entire career.

“Before, I used to think ‘I’ve got to make something happen. I’ve got to do something.’ And you haven’t really. If you try too hard at the game you’ll make wrong decisions. So, from that point on I just tried to play the game simple. My running power enabled me to get up and down; get crosses in, and have shots. For a fullback, those things alone were a plus.”

Below: John Ryan lets fly.

John

had finally come into his own as a professional footballer — he had

coaches who valued his intelligence and adaptability, teammates who

respected his work ethic, and a sense of confidence and self-belief that

had been hard-won. Needless to say, John’s decision in 1969 to turn

down Ipswich and seek a better deal on more money that accurately

reflected his talent was the decision of a lifetime. But at the time, it

was not supported by John’s most important backer — his father.

“The

day I decided to play for Luton I went home and told my dad, ‘I’ve

signed for Luton!’ He was confused — he wanted to know why I didn’t sign

for Ipswich. I told him that they wouldn’t give me enough money — Luton

did. He said — and this really summed up my dad I suppose — ‘John, if

you had signed for Ipswich I’d have given you the money.’ I said, ‘Dad, I

didn’t want the money from you, I wanted to earn it on my own.’”

Over

the course of John’s early life and career, no one believed in him more

than his father. In fact, his dad believed in John more than John

believed in himself.

“Dad

thought he could do anything. But not just himself, he thought people

could do anything. When I got into my football career we had many raging

arguments — because early on I didn’t think I was good enough; he did.”

In

1969, Ipswich was in the First Division, while Luton was in the Third

Division — having recently been promoted from the Fourth Division at the

conclusion of the 1967/68 season. For Sydney Ryan, the Third Division

simply wasn’t good enough for his son; he knew John’s talent was fit for

the highest level of English football. In the long run, Sydney was

right — John was better than the Third Division. But what Sydney had no

way of knowing when John signed — what no one really could have known —

was that Luton Town was on the rise too.

Luton

entered the 1969/70 season with a strong squad that was picked by many

to do quite well after finishing third in the league the year prior. The

addition of John and, perhaps most importantly, Malcolm Macdonald, all

but secured their promotion. Macdonald’s signing — another Harry Haslam

special — showed stunning foresight from the scouts. In Macdonald, a

young and unproven fullback at the time, they saw the potential to be

one of the best center forwards in England.

Ultimately, Macdonald scored 24 league goals, John established himself as a consistent, reliable starter and fan favorite, and Luton comfortably won promotion to the Second Division with a second-place finish in the league.

John,

for all of his charisma and natural magnetism, was not one to get swept

up in the moment. Instead, for him, promotion was simply the result of a

job well done.

“It

was great…” said John with a shrug. “…I always just wanted to do my

best for me, my team, and my future. People forget that it’s a job. And

you’ve got a responsibility to do a good job.”

Given

John’s no-nonsense mentality, and the increasingly high level of the

team, he had the reasonable expectation that the club would earn

promotion by season’s end. But by the penultimate fixture of the year,

Luton still had everything to play for. Indeed, they needed at least a

draw to secure their place in the Second Division for the following

season. And it was that game that sticks out most in John’s memory — not

for the exceptionally high level of play, but for the sheer chaos of it

all.

“The

only thing I remember about that season was the game against Mansfield

when we clinched it. It was the worst game of football you’d have ever

seen. We just kicked it as far as we possibly could and chased after it.

It was terrible. Drew nil-nil, it was hopeless. But we were up! That’s

it, job done.”

Four

years later, with Luton now in the Second Division and pushing for

promotion to the First, the club found themselves in the same situation:

needing a draw in the penultimate game of the season to secure their

place in the top tier of English football. And yet again, the manager

opted for a safety-first approach to getting the result. It worked.

John, perhaps more than anyone else on the day, took Haslam’s tactics to

heart and played the most cynical football of his career.

“We went to West Brom needing a point to go up. And I was marking Willie Johnston, who was a little Scottish winger. I was playing at right back and absolutely kicked lumps out of him. He was a fiery little devil too — he wanted to fight and everything. He said, ‘What the fuck are you doing?!’ I said, ‘Willie… we get a draw and we go up man!’ He went, ‘Oh! That’s alright then!’ So we drew 1–1. And that’s the main thing I remember about ‘73!”

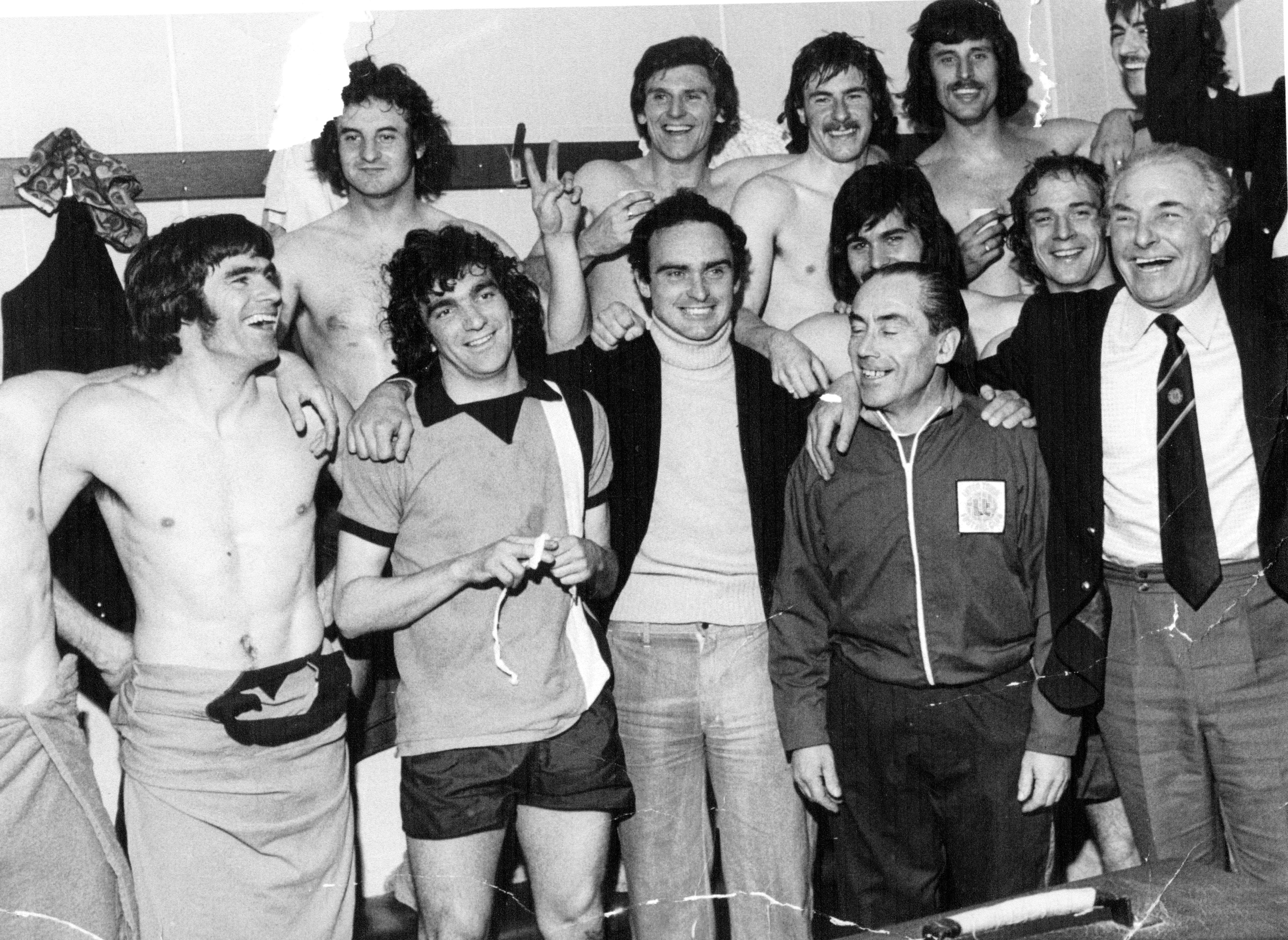

Below: John Ryan (front row 1st from left) and Luton Town after the West Brom game in 1974.

Luton

began their campaign in the First Division with the same core of

players that won them promotion — and understandably so. Several of them

had experience playing in the First Division from earlier in their

careers, and those that didn’t were among the best at their respective

positions in the Second Division. Unfortunately, the group that had

served them well the year prior got off to a horrible start to the

‘74/’75 season.

“Up to Christmas, we were hopeless,” said John.

But when 1975 rolled around, something clicked.

“After Christmas, we had a fantastic run. We had a really, really good team. In the end, it came down to the last game of the season.”

Below: John Ryan tries to find a way through.

Given

Luton’s poor form in the first half of the season, they needed help

from other teams to stay up. Unfortunately, that help didn’t come. Luton

needed Leeds to beat Tottenham in the final week of the season, but

Leeds sat their starters — opting to preserve their legs and fitness for

the cup final the following Saturday. So Tottenham won the game, and

Luton were relegated.

“We were very unlucky to come down in the end,” said John.

Unlucky

though they were, Luton was now back in the Second Division. And so

began the slow, but inevitable, dismantling of an otherwise great Luton

side. Over the next two seasons, many of the core players who anchored

the promotion in ‘73/’74 and the admirable fight for First Division

survival in ‘74/’75 were sold or released to make room for the next

generation of Luton Town football.

Peter

Anderson, for example, was sold to Antwerp in Belgium in December of

’75. Jimmy Ryan played his last game for the club on New Year’s Day of

1977. And John was sold to Norwich at the end of the ’75/’76 season —

one full year after Luton’s relegation back to the Second Division.

John’s

seven phenomenal years of service to Luton Town Football Club were

defined, first and foremost, by a resolute devotion to the craft.

“There

are certain traits to being a professional. And one of them is

persistence. I played with lots of young kids — as I came up the ladder —

who were much better than me, but never made it. They missed the key

ingredient. Bags of talent — they just didn’t have the grind I suppose,”

said John with a shrug. “You have to come into training five days a

week, snowing, raining, cold. You just got to keep getting out there and

doing what you do.”

Through his hard work, dedication, and persistence, John turned himself into the ultimate Swiss Army knife at Luton. Indeed, over the course of his seven-year tenure at the club, he performed with distinction at right back, center back, center midfield, and center forward. Whatever the team needed, John Ryan provided; whenever the squad had a problem, John Ryan was the answer; and whenever a match tilted toward uncertainty, John Ryan found the margins that mattered.

Below: John Ryan in an attacking role scores with a flying header.

He

was, inarguably, a Luton Town legend. But the end of his time at Luton

did not mark the end of his career. And, counterintuitively, at the age

of 29 — when most footballers begin to decline — John was about to

embark on the best years of his career.

In

August of 1976, John Ryan was sold to Norwich City for £60,000. By that

point, Norwich had been tracking him for a couple of seasons, and with

Luton back in the Second Division and unable to satisfy John’s

reasonable request for an increase in wages to match his true

footballing value to the club, the time was right to pull the trigger on

the transfer. John Bond, Norwich’s then manager, was pleased to acquire

a new starting fullback. But what he didn’t know at the time was that

John would ultimately make his greatest impact on the side further up

the pitch.

“I

went to Norwich as a fullback to start with,” said John. “So I played

the first season in defense. But after that everything changed. That’s

when I got coached. John Bond was brilliant. John Sainty was there as a

coach too. They were both good. And they just explained the game to me.

So I ended up being a much better player for Norwich than I was for

Luton.”

After working with John in individual training sessions, Bond and Sainty realized that his best position for Norwich wasn’t fullback — it was center midfield, as the engine room of the team.

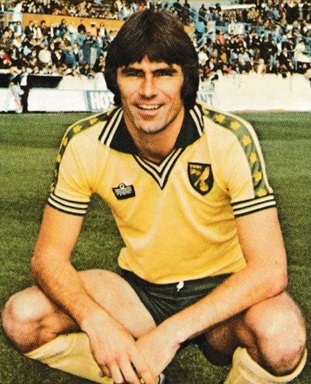

Below: John Ryan at Norwich.

“Norwich

was struggling for power in midfield. They had some great players, but

they lacked a bit of force. They weren’t strong runners. They had Martin

Peters who was coming to the end of his career. Graham Paddon had

broken his leg. So John Bond said to me, ‘I want you to play in

midfield.’ I was fine with that. But first I said, ‘The only thing, John

— I’m not Martin Peters. I’m not Graham Paddon. And I’m not Mick

McGuire. I’m John Ryan and I’m a runner.’ He said, ‘Yea yea, that’s

fine. Put yourself about.’”

Now,

with the opportunity to impact the game across the entirety of the

pitch, John was ready to make his presence constantly felt by teammates

and opponents alike. He announced himself immediately in a fixture he

remembers fondly to this day.

“So

my first game in midfield was against Arsenal. This is where karma

comes in — I scored the only goal of the match and we won 1-nil.

Obviously Billy Wright was no longer there, but I wanted to send a

message — ‘you should’ve kept me.’”

That

goal against Arsenal was the first of many he would go on to score in a

Norwich shirt. Ball-striking and goal-scoring had always been two of

his greatest strengths, but they were strengths he seldom got to

showcase when playing in defense. Now, with the license to crash the box

and shoot at will, the John Ryan of old was back — and he scored with a

ferocity and flair that would have made his father proud.

“By

the Christmas of ’78 I was one of the top goal scorers in the First

Division — Kenny Dalglish, Bob Latchford, John Ryan. And I was doing

this from midfield. They were forwards. And I scored some fantastic

goals. I was really smashing them in. I wish TV coverage had been then

what it is now, because some of the goals I scored were just… worldies.”

Given

John’s remarkable level of production, he figured he was due for a pay

raise. And so, he decided to give John Bond a visit to request one.

John’s logic in this regard was straightforward:

“If I don’t get big money now, playing the best I’ve ever played, I’ll never get it!”

John Bond, for his part, agreed. The Norwich City board, however, was less convinced.

“They thought I was too old. They thought I was finished, for some reason.”

John,

undeterred, was determined to get paid on the terms his performance had

earned. So, when he received the news from the manager that the board

were unwilling to increase his wages, he requested a move away from

Carrow Road. The timing couldn’t have been better — for the nascent

North American Soccer League had two clubs that wanted John’s services:

the New England Tea Men and the Seattle Sounders.

Seattle

was eager to give him the contract he requested, but it was a special

arrangement they were open to facilitating that ultimately sold John on

the Sounders.

“Jimmy

Gabriel was managing Seattle at the time. And he came down to Norwich

to see us. We discussed wages and signing-on fee, which I thought were

acceptable. Then I told them, ‘You only play March till August. Manager

John Bond wants me to come back and play here outside of those dates.’

They thought about it for a second, then agreed.”

John, ever the astute negotiator, decided to push a bit further:

“I

said, ‘Great… and I want pay for 52 weeks of the year from Seattle.’

They were unsure of that one. Then John Bond stepped in and said, ‘Jim,

fucking give him the money. He’s worth it.’ Jimmy Gabriel went, ‘Okay.’

So I got paid 52 weeks by Seattle and another 36 weeks by Norwich.”

And with that, John Ryan was off to America to play soccer for the Seattle Sounders.

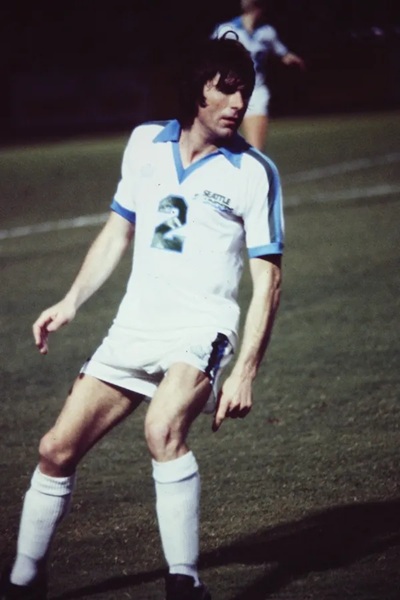

Below: John Ryan with the Seattle Sounders.

While

the football in America was most certainly below the level of the

English First Division, John enjoyed his time in Seattle immensely.

“I

loved the lifestyle in America. It was great! The crowds were excited

and the weather was great — even though they say it’s supposed to rain

all the time in Seattle, it was always sunny for us!”

And on the pitch, Seattle had one of the best teams in the league.

“The

only team I played in that I thought was too good for their competition

was the Seattle Sounders. We played 32 games and won 24. It was the

NASL record,” said John. “That team was magnificent.”

After

two strong seasons at Seattle, John returned to England to play for

Sheffield United — managed by none other than Harry Haslam.

“Sheffield

United’s director came out to see me in 1980. Me and Alan Hudson got

him drunk as a skunk! This was a chairman of Sheffield United! He ended

up laying on a wall, comatose! Anyway, they signed me, and I went to

Sheffield United.”

Sadly,

John’s year and a half in Sheffield did not go well for the club. Harry

Haslam was fired after John’s first season, and the club was relegated

to the Fourth Division. Then, in the middle of the ’81/’82 season, John

got another call from a former manager seeking his services — this time,

John Bond.

“John

was coaching Man City at the time, who were top of the First Division,

just before Christmas. He asked if I’d fancy coming to play for him.

Transferring from the bottom division to the top? Yep, sign me up!”

John had seemingly been given a lifeline out of nowhere for one last shot at meaningful competitive football. He was ecstatic. But then, John Bond added a caveat to the deal that changed the entire tone of the conversation:

“He

said, ‘The only thing, John, is that you’ve got to be in Blackpool by 5

o’clock to sign, otherwise you won’t be eligible.’ It was 1 o’clock on

the same day when I took his call. And, he added, ‘I only want you for 2

games.’”

Apparently, Man City’s starting right back was suspended for three games and they didn’t have a backup on the roster.

While

the prospect of playing in the First Division again was certainly

enticing to John, signing a two-game contract was as close to a gamble

as any veteran could take. John Bond figured as much and added a

sweetener to the deal:

“You’ll be left out after two games…” said the manager, “…but I’ll give you a coaching job.”

John,

now 34 years old and nearing the end of his long, illustrious playing

career, very much liked the sound of that. So he took the deal.

Two

days after signing for City, John started at right back on Saturday —

as he’d been promised — and was awarded Man of the Match.

“After that, I played the last 19 games of the season in midfield.”

Those

19 games would be the final chapter of John’s playing career, and he

retired from professional football at the conclusion of the 1982/83

season.

“My legs had gone,” said John.

And

for a footballer who had so relied on work rate, athleticism, and

relentless running, it was the only honest way to walk away.

John

Ryan’s professional footballing career spanned 18 seasons and saw him

play for seven different clubs. And despite the doubts and reservations

he had about his potential as a teenager sacked by Arsenal and Fulham,

his father, Sydney, was right all along: he was, indeed, good enough to

compete and succeed at the highest level of the game.

Unfortunately

for John and his family, Sydney Ryan never got the opportunity to see

his son play his best football, as he sadly passed away due to

complications from a stroke in 1971. But perhaps he didn’t need to — he

had already seen enough to believe it was inevitable.

While

John’s career as a player ended in 1983, his footballing life was just

getting started. Over the next 20 years, he coached all across the world

in various capacities. From Manchester City to his boyhood club

Maidstone; from spearheading the youth development program in Thailand

to running a week-long training camp in the West Bank; from Director of

Coaching at Starfire Sports in Seattle to Director of Coaching at

Sonesoccer Academies in New Jersey — John Ryan never stopped giving the

game what it had once given him: purpose, belonging, and a reason to

keep moving.

Finally,

in 2006, after 40 years in football, John ended his lifelong love

affair with the game and retired to Spain. In the unvarnished,

sentimental words of Kay, his wife of over 50 years:

“There was never a dull moment.”

She wasn’t wrong — and John wouldn’t have had it any other way.

John Ryan's profile page, complete with well over 100 photos and articles and a full record of his career with Luton can be found here.

Thank you again to Joe Press for his kind permission in allowing us to reproduce this article.